Evaluating a balance sheet can help you make more informed decisions as an investor, better identifying assets that fit your specific needs and risk tolerance.

How are investments recorded on the balance sheet, and how can you read it as a potential investor? While a balance sheet might seem intimidatingly complex at first glance, the truth is that anyone can read these documents as long as you have the right tools. Read on to learn more about how to evaluate a balance sheet.

What is a Balance Sheet?

You may use a budget to track your expenses in your personal finances. You might break down your budget into multiple parts, balancing the income from your job with everyday expenses like rent, groceries and retirement contributions. You can think of a balance sheet as a type of corporate budget, showing investors how much money is coming into the business and how much the company spends on recurring and non-recurring expenses.

A balance sheet, sometimes called a “statement of financial position,” provides a snapshot of a company’s finances at any time. In the most basic sense, a balance sheet is a financial statement that you can use to cut through the chatter of market news and see how profitable a company is directly. When used with other types of fundamental analysis, a balance sheet can be an invaluable tool in selecting profitable long-term holds for your portfolio.

Before determining how to classify investments on a balance sheet, it’s important to understand what the investments on a balance sheet mean and refer to. The basic formula used to analyze a balance sheet is:

Assets = Liabilities + Shareholder Equity

The “balance” in the phrase “balance sheet” implies that the equation above will always be “balanced,” meaning that liabilities plus shareholder equity will always equal company assets. Suppose the asset value of a company is negative. In that case, it means that its liabilities outweigh the equity that shareholders have in the company — a relatively common position for startups and new tech endeavors.

Let’s take a closer look at why each of these components is crucial to the analysis of a balance sheet of a company.

Assets

In the context of a balance sheet, assets represent everything of value that a company owns or controls. Two major types of assets are listed on a balance sheet, including current assets assumed to be converted into cash within the next year and non-current assets not expected to be used up during upcoming company operations. Some examples of assets listed on the balance sheet include cash, inventory and the property and equipment used to perform daily operations.

Liabilities

Where do debt investments go on the balance sheet? The answer is the liabilities section. Liabilities are the obligations or debts that a company owes to external parties, including creditors and lenders. Liabilities may represent debt investments on a balance sheet, leading to a negative balance sheet valuation if shareholder equity does not surpass the debt. While an asset is an item that a company owns, a liability is some type of item outstanding that the company owes to another third party.

Like assets, liabilities on a balance sheet are divided into current and non-current liabilities. Current liabilities are debts expected to be settled within one year, while non-current liabilities are those with longer maturities.

Shareholder Equity

Shareholder equity describes the portion of a company's total assets belonging to the people who own shares of the company’s stock. In other words, if the company liquidates its assets to pay off all its liabilities, the shareholder equity portion is the dollar amount that would belong to investors. A healthy level of shareholder equity indicates financial stability, and may show that a company has more flexibility to avoid bankruptcy in the future.

Understanding Each Part of the Balance Sheet

A corporate balance sheet breaks into multiple parts in the same way your household budget could include income from multiple sources and expenses in short-term and long-term categories. Let’s take a closer look at what to look for on balance sheet when investing.

Short-Term Assets

Where do investments go on a balance sheet? Depending on how long the company expects to hold it, it could be in the short-term or long-term assets sections. Short-term assets, also called “current assets,” are highly liquid assets a company expects to expend within one year. These assets are usually listed first on the balance sheet because items are organized by liquidity.

Some examples of short-term assets you might see on a balance sheet include:

- Cash and cash equivalents: This is the most liquid asset and includes cash on hand and highly liquid investments that can quickly convert to cash with minimal risk of price change. These usually include short-term treasury bills, money market funds and highly liquid marketable securities.

- Accounts receivable: These represent amounts owed to the company by customers or clients for goods or services delivered but not yet paid for. Accounts receivable are current assets because they are collected within a short period, often within 30 to 90 days.

- Inventory: Raw materials, works in progress and finished products are all considered under the inventory category.

Other items might include current assets of a company include prepaid expenses, advances to suppliers and short-term investments in stocks the company plans to sell within the year.

Long-Term Assets

Long-term assets, often referred to as noncurrent or fixed assets, are not expected to be converted into cash within one year or one business cycle — whichever is longer. Long-term investments on a balance sheet have a longer useful life, intended for use in the company's operations over an extended period.

Examples of long-term investments on a balance sheet might include:

- Property, plant and equipment (PPE): This category includes all tangible items and pieces of real estate that a company uses in its business operations. Land, buildings, machinery, equipment, vehicles and furniture investments are all under the PPE umbrella.

- Intangible assets: Intangible assets lack physical substance but have value to the company. Examples might include patents and software licenses.

- Long-term investments: In the same way you might hold assets in your retirement account for over a decade, companies might invest a portion of their funds in long-term assets. Common examples might include stocks of other companies and mutual fund investments.

Long-term equity investments on a balance sheet represent a company’s ability to generate income and can be an important consideration for investors. A positive trend of increasing long-term equity balance sheet valuation might indicate a growth stock.

Short-Term Liabilities

Short-term liabilities, sometimes called “current liabilities,” are obligations or debts a company expects to settle within one year or one operating cycle. Think of these as the debt-based counterpart to short-term assets. Some common examples of short-term liabilities include accounts payable and accrued expenses.

Long-Term Liabilities

On the opposite end of the spectrum from short-term liabilities are long-term liabilities, debt obligations that companies do not anticipate they will be able to pay off in the coming year. If you see a significant negative investment on a balance sheet, it is likely a long-term liability. The most common examples of long-term liabilities include long-term loans and commercial lease agreements.

How to Read and Analyze a Balance Sheet

Analyzing a company’s financial statement helps you recognize a strong balance sheet that’s more likely to signify success. Be sure to consider the following data points as you read a balance sheet, which you can calculate using the financial data you find.

Current Ratio

The current ratio is a liquidity ratio that measures a company's ability to cover its short-term liabilities and debts using its liquid assets. You can calculate a company’s current ratio using the following formula:

Current Ratio = Current Assets / Current Liabilities

A current ratio above 1 indicates that a company has more current assets than current liabilities, suggesting it is in a strong position to meet its short-term obligations.

Quick Ratio

A quick ratio calculation can be useful when you’re looking to identify assets using the strictest liquidity standards. The quick ratio formula excludes inventory from current assets because inventory can be less liquid and may not be easily converted to cash in the short term, calculated as follows:

Quick Ratio = (Current Assets - Inventory) / Current Liabilities

The “quick” in the name “quick ratio” refers to the speed with which assets can be sold.

The Cash Conversion Cycle

The cash conversion cycle (CCC) measures how long a company can convert its investments in inventory and other resources into cash received from sales. You can calculate CCC using the following formula:

- CCC = Days Inventory Outstanding (DIO) + Days Sales Outstanding (DSO) - Days Payables Outstanding (DPO)

Where:

- DIO measures how long inventory is held before being sold.

- DSO measures how long it takes to collect accounts receivable.

- DPO measures how long the company takes to pay its bills.

A shorter cash conversion cycle indicates more efficient working capital management and quicker access to cash. Investors typically prefer companies with shorter CCCs, as it reduces the risk of cash flow problems and improves overall liquidity.

The Fixed Asset Turnover Ratio

The fixed asset turnover ratio measures how efficiently a company uses its assets to generate revenue, and its formula is as follows:

Fixed Asset Turnover Ratio = Net Sales / Average Fixed Assets

A higher fixed asset turnover ratio indicates that a company can generate more profit with fewer resources, which could indicate positive resource management. It suggests that a company sees a higher dollar-amount return per dollar spent on resources, which sometimes signals higher sustainability.

Return on Assets (ROA) Ratio

The ROA ratio measures a company's ability to generate profit relative to its total assets, and offers a more general figure when compared to the fixed asset turnover ratio. It’s calculated using the following formula:

ROA = Net Income / Average Total Assets

The ROA is more inclusive than the fixed asset ratio, including revenue generated from tangible and intangible assets. Since average ROAs vary by industry, this figure is most useful compared to peers within the same industry.

Intangible Assets

Intangible assets are resources that hold value for a company but don’t have a physical form you can touch. For example, a corporate patent might be objectively valuable even though it is the legal status of the patent and not the piece of paper the patent is printed on that maintains value. Other common examples of intangible assets beyond patents include brand names and intellectual property.

Example of Evaluating a Balance Sheet

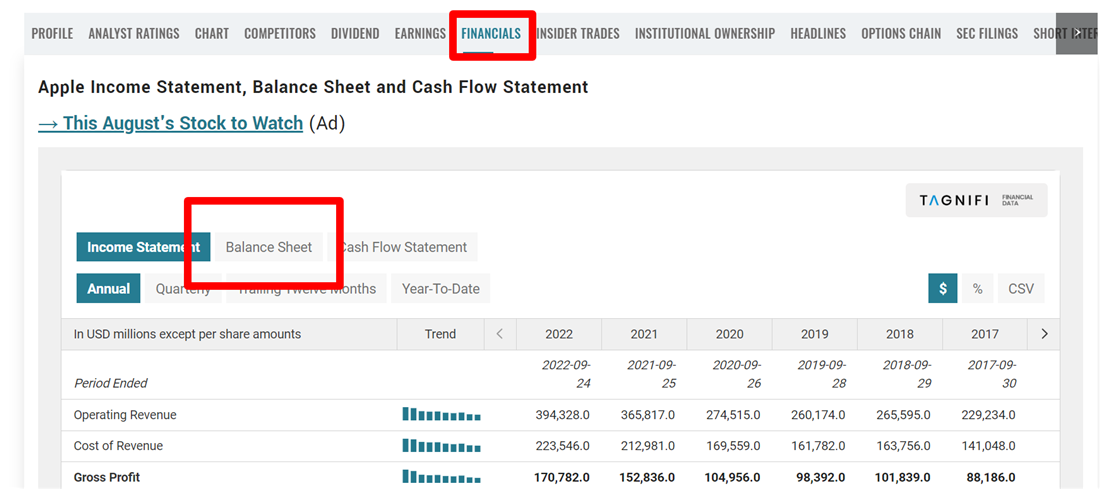

Evaluating a company’s balance sheet starts by directly accessing the document’s values. MarketBeat’s stock directory is a free and convenient way to view corporate balance sheets. Simply navigate to the stock’s page, click the “Financials” tab and navigate to the most recent balance sheet.

Data from corporate balance sheets compares past data and data from competitors. MarketBeat makes it especially simple to compare trends over time by listing data pulled from previous balance sheets side-by-side with current data.

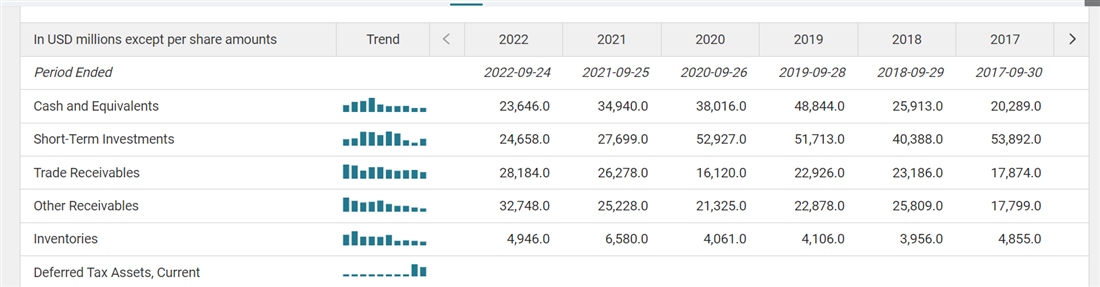

For example, as you can see from Apple’s NASDAQ: AAPL most recent balance sheet, the company has a total of $23,646 million in 2022 — but this figure represents a downward trend. This signifies that Apple has been tapping into its cash reserves recently, which investors would want to investigate the cause of before buying the stock.

What Does a Healthy Balance Sheet Look Like?

When evaluating a balance sheet, the most important thing to remember is to compare the data you find with the right alternative corporate statements. Items like outstanding liabilities and cash flow can vary widely between industries, making comparing companies from different sectors less useful. Review balance sheets from companies you’re invested in as you receive them to ensure that your portfolio still lines up with your goals and risk tolerance.

Before you consider Apple, you'll want to hear this.

MarketBeat keeps track of Wall Street's top-rated and best performing research analysts and the stocks they recommend to their clients on a daily basis. MarketBeat has identified the five stocks that top analysts are quietly whispering to their clients to buy now before the broader market catches on... and Apple wasn't on the list.

While Apple currently has a "Moderate Buy" rating among analysts, top-rated analysts believe these five stocks are better buys.